Listen To Your Body and Find Your Purpose

Marling’s journey toward becoming an artist didn’t begin right away; in fact, she had a career as a financial analyst prior to working in the film industry. Feeling unfulfilled with the demands of the stock market and the pressure to have a “survival job”, Marling decided to leave it behind for the hustle and struggle of being an artist in Los Angeles. “What I found in that period when I was working at the bank was that other people seemed to like what they were doing, but I felt, in my body, this intense fatigue and my chest felt tight…My parents are proud of me for even getting my foot in the door like this. It means financial security and it means safety and all these things that we all, of course, value. But my body was telling me a different thing.”

Listening to your body and your intuition, Marling explains, is the first step in uncovering what is important to you as an artist and what kind of stories you long to tell. It can be as simple as taking ten minutes to yourself in the morning and finding a sense of stillness to let your feelings speak to you. “If you feel grief, let it come out in its weird ways. I think that that’s part of uncovering your vocation or what it is that you sense deep within you. You learn what you might be capable of and what you might have to give.”

Filmmaking is an incredible discipline for acknowledging how much we can achieve when we cooperate together.

Artists – and Everyone Else – Need a Community

Marling learned to live modestly, pursue her passion and most importantly, create a community around her. “We were all living together in a house and we were trying to make things and we were writing and rewriting and editing and re-editing short films,” she says of her early days living with friends in Los Angeles. “We would get small jobs doing gigs and reality TV shows and that would pay the bills for a while, but we were always nurturing the sort of tidal pool of ideas between the three of us, and I think if we hadn’t had that early ecosystem, I’m not sure we would have survived that transition.”

Especially early on in your career, finding collaborators often comes down to vision. “A lot of it in the beginning is about finding people whose imagination and mind stirs yours,” Marling says. But the need for a supportive creative community is one that will remain throughout the years, and that community will evolve and grow with you as an artist. Marling adds that learning to communicate with your collaborators also means learning humility, understanding how and why their vision may be different from yours and learning to admit when you’ve been wrong.

It’s not always easy, but the payoff to working together can be significant. “That is such a high when you achieve it, because it’s not about any one individual or ego at all. It’s about a group coming together and somehow transcending even the sum of their parts to get at something else. It doesn’t happen that often, but that’s the feeling I think that I’m always in search of and that I encourage other young filmmakers to go and search for.” She advises, “Check your ego at the door, find a group of people who are like-minded who want to try new things and then see what you can do together because it’s always going to be so much more interesting and what you can do on your own.”

Find a Genre That Welcomes the Stories You Want to Tell

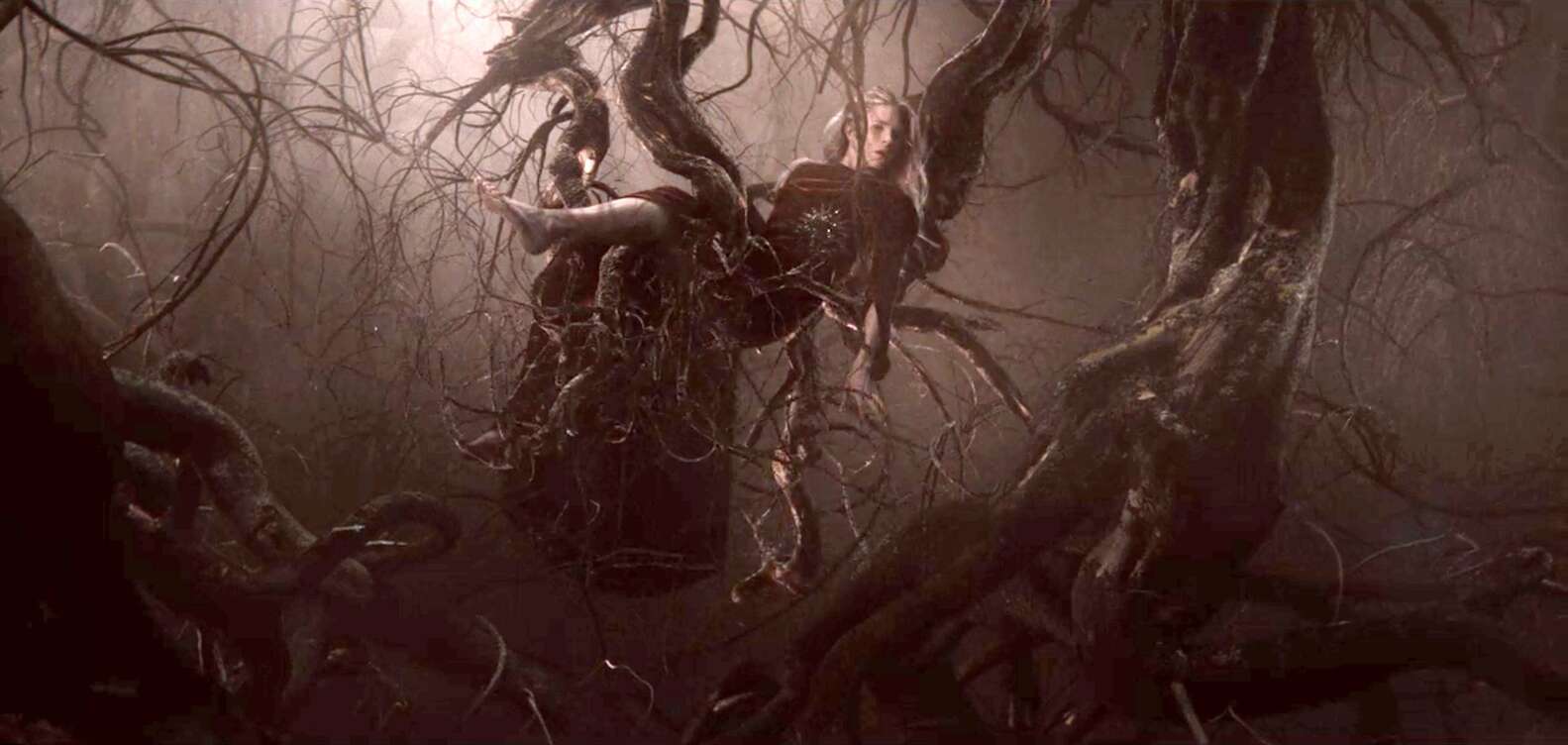

The emphasis on community is one that has stayed with Marling throughout her career and has come through as a common theme in her work, particularly on her acclaimed Netflix series, The OA, which she co-created and also stars in. A science fiction story about a group of young adults who have survived near death experiences (referred to on the show as NDEs), the strength of the bond between multiple characters is the central point of the show’s narrative. She explains, “We’ve all taken hold of this Darwinian idea of survival of the fittest, and certainly our economy and a lot of our macro narratives for how we live our lives are based on this idea. That actually isn’t how nature operates. Nature’s actually ‘survival of the most cooperative.’ That’s what lives in a forest: interspecies communication, collaboration, cooperation. I think that’s a powerful message for this time that we’re in, in which we’re seeing how much we need one another and how much we have to support one another.”

Marling didn’t have a particular interest in science fiction when she began her creative career. Rather, her move into the world of sci-fi—first with her feature film Another Earth—came from her experience acting and becoming discouraged with the kind of roles for women she read during auditions. She often felt that they were “as dispiriting as investment banking.”

Discovering female science fiction authors such as Octavia Butler and Ursula Le Guin was eye opening to her as a woman trying to pursue her passion. “I found that the real world was very challenging to write women in because you were always dealing with the very real circumstances of patriarchal oppression, so there was no way to write a story set fully in the real world that wasn’t constantly having to address that. And I think what science fiction made me feel was this permission to be just outside of reality and it helped me as a writer to just relax a little, and be like, oh, it can actually be whatever I can imagine.”

Reframe the Narrative From Your Own Point of View

In addition to the pressures of the world around us, there are the views and structures we have all internalized in the media to consider as well. “We’ve taken in so many narratives written and directed and performed by men. As young women growing up, we’ve learned to suture to a male protagonist and to see the world through their eyes. So we don’t actually know that much about the female perspective because women haven’t been writing for that long. We’re often aping the works of men that have come before us when their structures are different.” Creating a strong female lead, she says, “isn’t just taking the male action hero, plugging a woman in it and making some sort of nod to her being a woman by having her find a maxi pad in the bathroom and use it as a wound compress.” In early 2020, Marling even published a column for the New York Times about her process of crafting narratives from the female perspective, appropriately titled “I Don’t Want to Be the Strong Female Lead.”

Framing a story’s narrative from the male perspective is incredibly common in the world of storytelling, whether explicit or implicit. Part of the job as a creator is to recognize and challenge those perspectives when they show up in your own story. Part of that perspective includes writing about a sense of community. “I am excited by the challenge of trying to write about women that feel strong in ways that aren’t always with a machine gun or a knife. It can be that there is strength in how women work often in a community, it can be that there’s strength in intuition, which is a lot more of a sort of softer, stranger thing to follow than just linear rigorous intellect. It can be that there’s power in dreaming and daydreaming and wild imagination which are all sort of softer, or abstract forms of intelligence. I wrote the piece to encourage myself to keep digging for it, but I think it’s a dig we’re all on together.”

The leap of faith Marling took to be an artist is one that has paid off substantially for her. The opportunity to explore the depths of human nature and expand the perspectives we as an audience see in the content we consume can be a rewarding experience that continues the important work of artists who have come before us.

Marling also emphasizes that evolving as an artist takes time, and that up and coming artists need to learn to give themselves space to explore and grow. “I think in this culture we tend to really tragically, falsely not only just promote the individual but promote this idea of an artist’s sort of springing fully formed at 21,” Marling says. “For most of us, that is not the case. When I moved out to Los Angeles, I must have been 23. It was four years of just working odd jobs and writing things that weren’t very good or couldn’t get made, and it’s okay for that amount of time to pass. I think sometimes we’re made to feel this urgency that other people around us are doing it or other younger people have done it, and I would say just let go of all of that. However much time you can give to yourself in a day, give it to yourself and see if you can get quiet enough to hear what’s inside, because nobody can really offer you advice. That’s the thing I’ve finally internalized: you are your own best advisor. So if you can get quiet enough to hear it, you actually know what you should be doing and what you are capable of doing.”