What Do You Want to Say?

According to Porter, making a documentary film will always begin with your first major question: what do you want to say? She is often asked about the mission behind her stories, as some documentary filmmakers choose to take more direct action for social change. It’s always a personal choice for each filmmaker, but Porter says, “I consider myself a curious person who has storytelling skills,” rather than a social change agent. Her background in journalism has helped shape her style of filmmaking, and she prefers to present the story as it is and share it with those who have the ability to push for social change, rather than be the one to solve the issue herself.

In defining your goals, finding your subjects, and shaping your story, it’s important to remember that the documentary process is likely going to be a long one, and you need to be prepared to commit at least two years to the project. With that in mind, it’s essential that your topic is one you are willing to be fully invested in for a significant amount of time. As you begin to put together a plan for your early shoots, you should identify your first major goal and create a plan in service of that goal.

Other factors to consider early in the development process:

- When you begin filming, you may need to see others reacting to your subject as well as the subject themselves. Who else in their lives or in this environment should be present when shaping the story?

- Determine when is the best time to access someone’s story. If, for example, your subject is a mother with young children, going to her home after school and before dinner time may not be the best time for an interview.

- Match your story with a proper location and know when and where to place your subject, always in service of the story you want to be telling.

- Finally, Porter suggests that by the time you’re about 25% of the way through filming, you should be able to define whose voice specifically is telling the story. This brings us to the next important question in your early filmmaking process:

Are You the Right Person to Say It?

An essential question to ask yourself, Porter shares, is: “Do I have the curiosity, the capacity, the interest, and the background to either bring something to this story or admit that I don’t know and bring others into this process with me?” As the creative force behind your story, a fundamental part of the early process will be to define what part of you and your own authentic voice will shine through in the film.

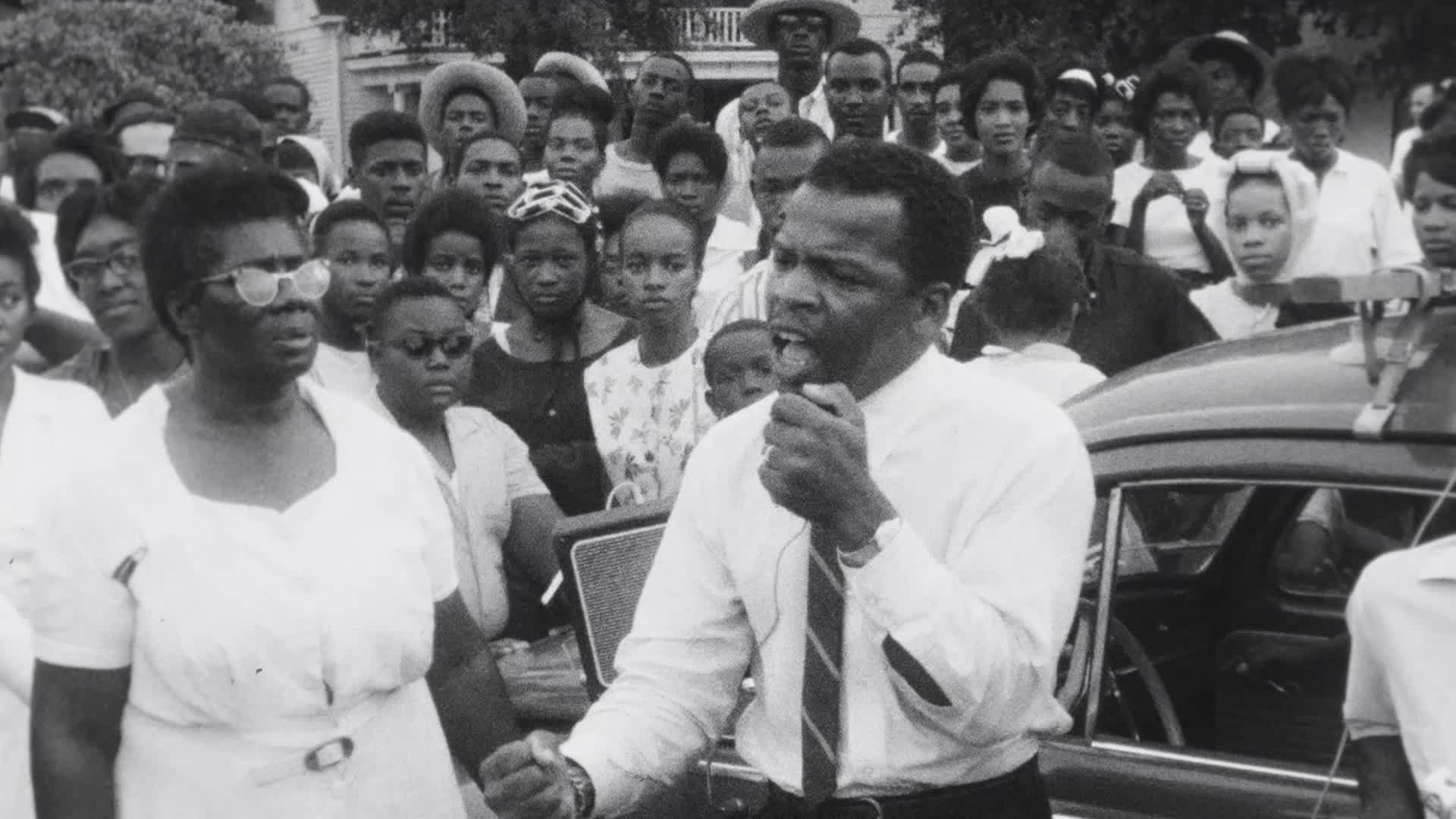

When she began working on John Lewis: Good Trouble, Porter wanted to explore older archival footage of her protagonist, Senator Lewis, in hopes of telling parts of his story that hadn’t yet been as well covered. Noticing that he was often described as “brave,” she wanted to show the world that he was also very strategic, which she realized that she could add using footage from his student years. She recalls, “We should see him as a student studying and planning. It enriches your understanding of the subject.” Similarly, while developing Gideon’s Army, she brought her own experience as a former lawyer to the project, and was willing to learn the differences between being a corporate lawyer, as Porter had been before venturing into documentary filmmaking, and being a public defender, like her subjects in the film.

Porter notes that it’s inevitable that you as the storyteller will have a certain perspective shaped by your own experiences, and there will be times when you should bring in others, perhaps those who are closer to the community whose story is being told, who can help you shape the story in the most authentic way possible. “There are ways to invite people in,” Porter explains, “but you have to have an executive session with yourself to define your needs and your wants and to be honest with the people you’re trying to bring into your world.”

Usually, our guts are right.

Dawn Porter Tweet

Where Does the Story Begin?

Much of filmmaking is certainly a labor of love, but It is difficult to find the space to develop a story without being paid. Porter’s advice is to be honest with funders in the early stages of development that you will need adequate time to explore the story prior to filming. With that in mind, development begins with coming up with your story and researching it.

Porter suggests that you start with an animating question in your mind when developing a new story and subject. What is a fundamental and valuable question that will allow your subject to speak openly and comfortably about their experience? For example, the idea for Trapped came while Porter was making another film in Mississippi and read that the one remaining clinic in the state that could provide abortion services was in danger of closing. She thought, “If I don’t know this information, others probably don’t either.” She approached several health care workers with an idea for a documentary, and from there, asked the key question: “What does it take for this clinic to stay open?” That ended up being the question that is answered through the course of the film.

Another key piece of advice: lean into doubts. What are they? You might need to do a really big pivot in the focus of the project, and it’s best to do it as early as possible. As Porter says, “Usually, our guts are right.” You are going to put an immense amount of time and money into your project, so “The last thing you want is for someone to take the air out of that bubble the second it’s publicly displayed.”

Your voice, your story, and your key question should be coming through in your work, so it’s also important to listen to feedback to be sure others are understanding your message. Though you don’t need to implement or follow through with the notes you receive, you need to be sure to respect the time and feedback others are willing to give.

How Can You Establish Trust with Your Subjects?

The most important thing when reaching out to potential film participants in the early stages is to be open and clear about your interest as a filmmaker. Be aware that you are the one who knows about the process, and your subjects likely won’t, so be sure to spend plenty of time with them in person and explain what you think the process will be. Give them a sense of length, funding, and time commitment, and be conscious of when the right time will be to have them sign releases.

Working with a subject of a documentary always comes down to trust. It is a filmmaker’s responsibility to build that trust early on, not just in their own relationships with their subjects, but among the crew as well. When filming Gideon’s Army, the project’s Director of Photography, Chris Hilleke, was able to capture some very personal moments with their subjects simply because they had put in the time to get to know each other, and the subjects didn’t feel uncomfortable crying or being open and honest in front of the camera. Just as you need to be prepared to work on a project for several years, the subjects also need to understand and feel comfortable with that kind of a time commitment.

Above all, the protection and safety of yourself, your subjects, and your crew is the most important responsibility—and one of the largest complications—you will have as a director. Some situations Porter encountered while filming Gideon’s Army, for example, could have compromised attorney/client privilege, and thereby endangered someone’s ability to have honest conversations with their lawyer. Keep in mind what you need to show in your story and what the repercussions of those decisions can be. Whatever you decide, make sure you have done so intentionally so you can stand by it if and when questions arise in the future.

Should You Pay Your Subjects?

One of Porter’s few hard rules when it comes to her subjects is not to pay them for their participation in the film. It’s a controversial matter among documentarians, but Porter feels as though paying subjects sets the expectation that they will be performing for the camera, thereby compromising the authenticity of the story. With that being said, she does feel it is acceptable to pay for someone’s transportation expenses or for the use of certain archival materials, such as photos; photos in particular are necessary to the film and would need to be purchased through a library anyway, so directing that part of the budget toward an asset the subject owns is an acceptable expense. Porter explains, “If you make a good movie and people see it, the benefits that will come to your subject are so much more than if you had risked the authenticity of your movie by paying them a few thousand dollars.”

Money is also an important factor to consider when identifying ways to even out the balance of power between storytellers and their subjects. Considering their needs during filming is important, and you could, for example, offer to shoot in a location where a subject won’t have to drive very far, especially if it’s difficult for them to afford transportation. On a broader scale, you also need to consider portraying them as a subject without being patronizing. Porter’s advice is to focus on what your subjects and your audience will have in common, rather than opening their story with a filter of sympathy or pity for their situation.